”Who is a refugee?”

”A woman with a bike,crossing the way in Ritsona”

A refugee is someone who, once, had a normal life, a home for his family, a school for his children, a hospital. He enjoyed respect and dignity. He had friends, relatives and basic humans rights. He had dreams, hopes, plans for the future. What he did not have was safety. That was taken from him by political and economic games.

A refugee is that brave father and that courageous mother, who

pluck their courage to protect their family and choose to leave their

country and undertake a voyage with death lurking along the way.

A refugee is a person who struggles many years, in many

countries, his safety always threatened, his days filled with the

sounds of bombs and explosions. A refugee is a person who has

seen the hospitals and schools destroyed under fire.

A refugee is a person, who amid the bombs, the explosions, the

fires, he does not give up his hopes for a new life for himself and

his children, for safety, for peace, for nights with dreams rather

than nightmares. A refugee dreams of a day when the news do not

report numbers of killed or injured, do not recount bloody suicide

attacks.

A refugee is a human being who is as normal as thousands of

other human beings who constitute the population of this world.

The difference between him and those others is the place where

his luck decided he would be born.

A refugee is a mother who gives birth to children whose lives she

will not enjoy. She does not rejoice at their birth. A pregnant

refugee woman can listen to the heartbeat of her baby inside her,

but she cannot hear her child’s laughing or crying in the crowded,

noisy and chaotic world of refugee life.

A refugee is that powerful, courageous and freedom seeking

member of a family, who cannot accept that his rights and freedom

are repressed.

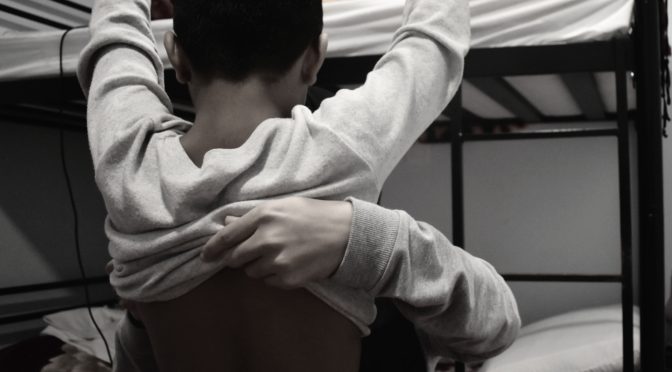

A refugee is an orphan child, a single mother, old parents,

vulnerable people, victims of wars who gathered all their courage

in a back pack and who, holding their children’s hands, passed

thousands of miles of distance, walked over mountains, often losing their way, tolerated hunger and thirst, crossed borders, faced all sorts of difficulties, including humiliations and indecencies

by border guards who treated them as criminals. The women,

among them, faced the worst physical violence, being raped not

only during the voyage, but even in the camps where they found

themselves enclosed. Those women did not face violence from

strangers alone. Even more tragic, they faced the violence from

their fathers, brothers and husbands, violence unleashed, in them,

by the horrible conditions of their lives.

Yet, in spite of all these hardships, a refugee is the one who did

not resigned, but held in the back of his mind the promise of light

that for millions of refugees was the light called Europe.

Thus a refugee is someone who after many failed attempts, after a

number of pushbacks, even deportations, insists on reaching that

promised light, that Europe.

And what does any and every refugee find reaching that promised

land of Europe? Certainly not a new life! What awaits him are

discrimination, inequality, repression, segregation as if prisoners,

exclusion and deprivation of the most basic human rights — all

these in a climate of total uncertainty about their future.

A refugee is a single woman, an unaccompanied girl who is put in

the so called “safe zones “ where life is threaten by those very

people who live inside such a zone. A refugee is single mother

living in a tent near a tent of men who drink alcohol and lose

control over their actions.

A refugee is a fighter who struggles to keep his hopes and not to

give up. Yet even those fighters can be defeated and find solace in

suicide.

But there are dreams behind their clenched fists, there are

demands behind their repressed voices. There are pains behind

their smiling faces. There is passion in their writings, there are

sparkles in their eyes, there are wings in their soul, there are

screams in their strained throats.

A refugee is a girl like me, who is writing every night what she

experiences everyday. Every night, before she falls asleep she

proclaims her dreams in the hope that she will reach them one day. She is fighting against injustice, like many who are fighting

against repression.